The Heckscher-Ohlin Room

The Stockholm School of Economics welcomed its first students in 1909, with the founding charter from that same year establishing the school’s objective as strengthening the competitiveness of Sweden through science-based teaching and research. Science is thus at the core of SSE’s identity. Science, theorizing, and academic thought is what the Heckscher-Ohlin Room is a celebration of and a tribute to. The room is located at the very core of the School. It has the most prominent location in the building, right above the entrance, and in the middle of the piano nobile, the bel étage. To manifest the importance of scientific approaches, the room is infused with the highest aesthetic quality and attention to detail. The room combines international design and works by internationally renowned Swedish artists. Along with a chandelier by Lindsey Adelman, chairs by Mario Bellini, a sofa by Konstantin Grcic, and tables by Piero Lissoni, there are artworks by Charlotte Gyllenhammar, Bella Rune, Christian Pontus Andersson, and Jens Fänge.

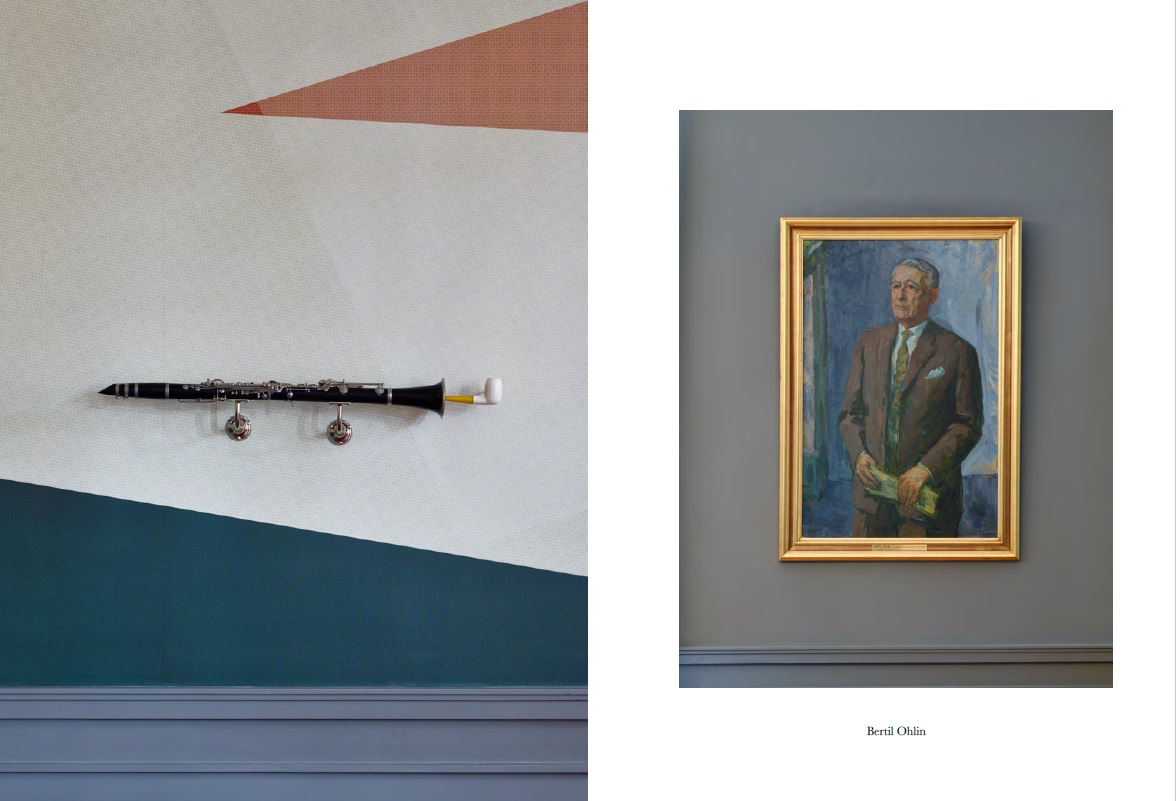

The room serves as our faculty lounge, where we gather for academic celebrations. When entering the room, you encounter portraits of two prominent former SSE professors: Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin. The latter was the 1977 recipient of The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, partly for his work in collaboration with Heckscher, who passed away in 1952. The chandelier hanging from the ceiling has an almost organic form, like an enlargement of a model of something you expect to find in nature – a model of a molecule or a depiction of something organic. The chandelier is a first hint to what this room wishes to convey: a feel for models and theories that aesthetically combines beauty and a quest for understanding our world. The huge wallpaper artwork by Jens Fänge both serves as a tribute to theory as to the history of our school. You will see depicted objects: a glass, a piece of paper or cloth, and a cigarette butt.

The aesthetics remind us of comic strips. In the world of comics, features of complex realities are elegantly reduced. By altering tiny lines, the cartoonist quickly makes a character angry, sad, or happy. A few lines and some extra colors simplify reality whilst performing a maximum in terms of both explanations and expressions. This is precisely what good theorizing does. It unveils the essence of a phenomenon. The task is to rid our vision of whatever blur it. The artwork in the room conveys that quest for clarity. Fänge has added a hand clearing and wiping away the smudge that obscures our understanding of societal structures. We can also see cues that speak to social scientists, like when Fänge makes Adam Smith’s invisible hand visible in a drawing. Or perhaps it is Eli Heckscher’s lifeless hand – a reference to his hand as seen in the oil portrait on the wall – as he departed before Bertil Ohlin received the prestigious prize? Fänge also presents an organic interpretation of the famous textbook graph of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem. The model sprouts, grows and almost seems to turn into natural science.

Fänge’s entire pattern is also consciously similar to the geometrical features characteristic of the works by 1950s Swedish concretist Olle Baertling. Fänge winks to Baertling: from the balcony outside the room you can see a steel sculpture by the latter on the lawn outside the school. Baertling on the outside communicates with Fänge on the inside. Fänge also plays with our wish to connect the dots, just like good social analysts do. We see a clarinet fused with a pipe. Two objects: you inhale from one, you exhale into the other. One is black, one is white. There is something similar in these two objects, but how do they come together? When René Magritte presented us with an image of a pipe and the accompanying explanatory text “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” he reminded us that this was not an actual pipe, merely a representation of one. Fänge’s pipe surely is a pipe. But it is also a representation of something else. The play with representations shifts our attention to one of the key questions of our time: what can we trust in this world of deep fakes, alternative facts, and machines creating words, images, and sounds that only have a vague connection to “truth”? Theories are linguistic artifacts of reality, constantly begging the question of what reflects what. You may ask how a pipe fits into a clarinet, as you may ask how a theory fits into reality.

Or, as Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s photograph Whiz and Bella Rune’s virtual projections, explore new surprising perspectives of otherwise taken-for-granted realities. Gyllenhammar turns the world upside down. Theorizing and analytical thinking require us to do exactly that: turn the taken-for-granted on its head. We are urged to pose the question: what if things were the other way around? Is the dependent variable, in fact, the independent one? What is hidden in what we regard as face value? When we use different tools, completely new realities are activated. This is what many researchers do: they apply tools to empirical material in order to discern something else. Technologies make us see the world in other ways. Without telescopes, there would be no insights into cosmos. Without microscopes, no insights into microcosms. Without digital tools, modern science would look very different. The Heckscher-Ohlin Room also reminds us of the charm of serendipity in science. Christian Pontus Andersson’s buffoonish chef figure surprisingly pops out of the wall. Research is not only structure, design, and careful analysis. It is also fun and unexpected, and the outcomes of scientific endeavors are sometimes utterly impossible to predict. The design and refurbishment of the room were made possible through the very generous support of Nordiska Galleriet. The artwork by Jens Fänge was made possible by the generous support by Lena & Per Josefsson, Elisabeth & Martin Wiwen-Nilsson, and Carl Hirsch.

Introduction by Lars Strannegård, President Stockholm School of Economics

The Heckscher-Ohlin Book

A publication has also been published with contributions by Mats Lundahl, Lars Strannegård, Pierre Guillet de Monthoux, Erik Wikberg, Bella Rune, Isak Nilson, Jens Fänge and Charlotte Gyllenhammar. Photographs by Mikael Olsson. Design by Maja Kölqvist and Carl von Arbin. Send a request to order here