Shifting lanes

In this article, Jonas Colliander and Sara Rosengren show how retail firms can come out of the COVID-19 crisis as winners. The authors note that when consumers find themselves in new buying situations, they often stick to the first brand they buy in a category, provided that they are satisfied. A crisis like this could, therefore, be an opportunity to gain market shares. Moving forward, the authors predict that consumers will desire simplicity and that sustainable business practices might not only be good for the environment, but also for business.

Jonas Colliander and Sara Rosengren

In 1966, Robert F. Kennedy delivered a speech at the University of Cape Town where he told an assembled group of students: “There is a Chinese curse which says ‘May he live in interesting times.’ Like it or not, we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also the most creative of any time in the history of mankind.”

As governments and companies struggle with both the human and economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, Kennedy’s quote could scarcely be more apt today. The increasing death toll reported from around the world testify to the dangers facing the most vulnerable in our societies. At the same time, bleak economic forecasts perfectly illustrate the economic uncertainty that lies ahead. Yet in crisis also lies opportunities, for both politicians and business leaders. Just as governments have the opportunity to shift the workings of the state during the current crisis, managers have the opportunity to change the course of their organizations to better suit the post COVID-19 business landscape. To do so, however, one typically needs a map. Fortunately, discussions are already underway among researchers, journalists, and practitioners about the lay of the land once we emerge from lockdowns and self-imposed social distancing. Areas as diverse as the security of supply-chains to the future of store designs are debated as never before.

This paper attempts to contribute to that discussion by providing insights on how consumer behaviors are affected by the crisis. More specifically, this is done by condensing research on consumer behavior during and after crises. Knowing how consumers behave is key for getting back to business once the current crisis has subsided. This is especially true for retailing, which by definition is focused on consumers. Retailers in Sweden and abroad can expect the consumer to emerge changed following the COVID-19 pandemic. Past research on consumer purchasing patterns during events such as natural disasters and economic downturns suggest that consumers often experience uncertainty and cut back on spending in favor of large amounts of necessities during a crisis. Past experiences from the SARS-epidemic in Hong Kong also taught us to expect a surge in e-commerce in the wake of the current pandemic. We conclude by discussing the opportunities that lie ahead by drawing attention to a little-known mechanism in consumer behavior called behavioral primacy, the tendency of consumers to alter consumption patterns during major life changes and their preference to stick to the first brands they choose in new product categories. This, we argue, presents an opportunity for retailers and brands. A lot of consumers are going through major life changes at the moment and are therefore trying out new product categories. Capturing these new category users should be a major strategic goal of companies since they are likely to remain at least partially loyal and could thus be assumed to contribute to a retailer’s bottom line for a long time.

Consumer behavior during crises

The current crisis has been called the most severe shock to society since WWII. Indeed, the many empty streets of normally buzzing cities that have become characteristic for the spring of 2020, and reflect the extraordinary measures taken by governments around the world to stem the spread of COVID-19. Similarly, the unprecedented unemployment figures bear witness to the economic hardships brought on by the virus. Whereas we can expect consumer behaviors to change as in recessions, we are simultaneously seeing specific changes caused by the lockdowns and health concerns in the population at large. Thus, in order to understand consumer behavior in times like these, one has to consider not only scientific literature about economic downturns, but also examine literature about consumer reactions to extreme events such as natural disasters and previous epidemics.

A review of this literature reveals that in times of crises, people tend to experience feelings of insecurity and anxiety, which leads most of them to spend less in total and buy more basic goods (in bulk). It has been demonstrated, however, that some consumers, especially at the bottom half of the income ladder, are more prone to impulsive and even compulsive buying during times of uncertainty.

Studies on previous natural and biological disasters indicate there are large social and psychological impacts of these events as well. These types of disasters also impact consumer behaviors. Studies on the 2003 SARS outbreak in Asia demonstrate increased levels of stress, anxiety, depressions and a general feeling of helplessness among the populations in affected areas. Likewise, studies on the effects of Hurricane Katrina, which hit the U.S. Gulf coast in 2005, show that a perceived loss of control over the situation led to increased levels of stress among those affected. With the current disaster playing out on a much grander scale, stretching of the imagination is required to surmise that those affected by COVID-19 will experience similar emotions.

These emotions, along with the direct economic impact caused by for example unemployment, lead consumers to spend less during crises. States affected by SARS experienced severe drops in earnings, particularly within the service industries. Hong Kong, for instance, experienced a 4% drop in GDP due to decreases in consumer spending and tourism. Estimates from Forrester research predict even more sever drops in retail spending as result of the current pandemic. Due to the coronavirus crisis, the firm predicted that global retail sales are expected to fall by an average of 9.6% in 2020, representing a loss of $2.1 trillion. It is expected that it will take four years to return to pre-pandemic levels. A survey of Swedish retailers by the Swedish Trade Federation confirms dire predictions as retailers themselves report much lower expected sales for 2020.

Not all consumption, however, is negatively affected by crises. Industries that cater to more fundamental human needs tend to see an increase in sales as consumers’ priorities change. Grocery retailers, for instance, often see sales go up as people stock up on fundamental supplies. Similar scenarios have played out during the current pandemic. Purchases in sectors such as fashion and beauty have shrunk as a share of consumer spending. According to the Swedish Trade Federation, fashion retail, for instance, decreased by 33,7% in April 2020 as compared to April 2019. The grocery and other essential consumable retail industries, on the other hand, were increasing their sales. The Swedish Food Retail Index, for example, shows a total sales increase of 6,7% in April 2020.

However, grocery retailers often experience other problems as consumers tend to shift towards buying different categories of goods in greater quantities. Bulk buying is typically an immediate reaction and a way for consumers to regain control in a highly uncertain circumstance. This was also evident in how Swedes reacted during the current crisis. In and ongoing project, we are investigating public reactions to the crises using data from different companies. Part of the data comes from grocery retailing where we could see this pattern clearly. Following a statement by the Public Health Agency of Sweden on March 10, which highlighted a high risk of the novel Coronavirus spreading domestically, consumers dramatically increased their grocery purchases the following ten days. Bulk-buying was more prominent in Stockholm (where the threat was the greatest) than in the rest of Sweden, with peak buying occurring 48 hours after the announcement. On March 12, sales at our collaborating retailer were up +74% in Stockholm (vs. +49% in Sweden overall). By the end of March sales had stabilized, although on a higher than usual level given that most people were spending more time at home.

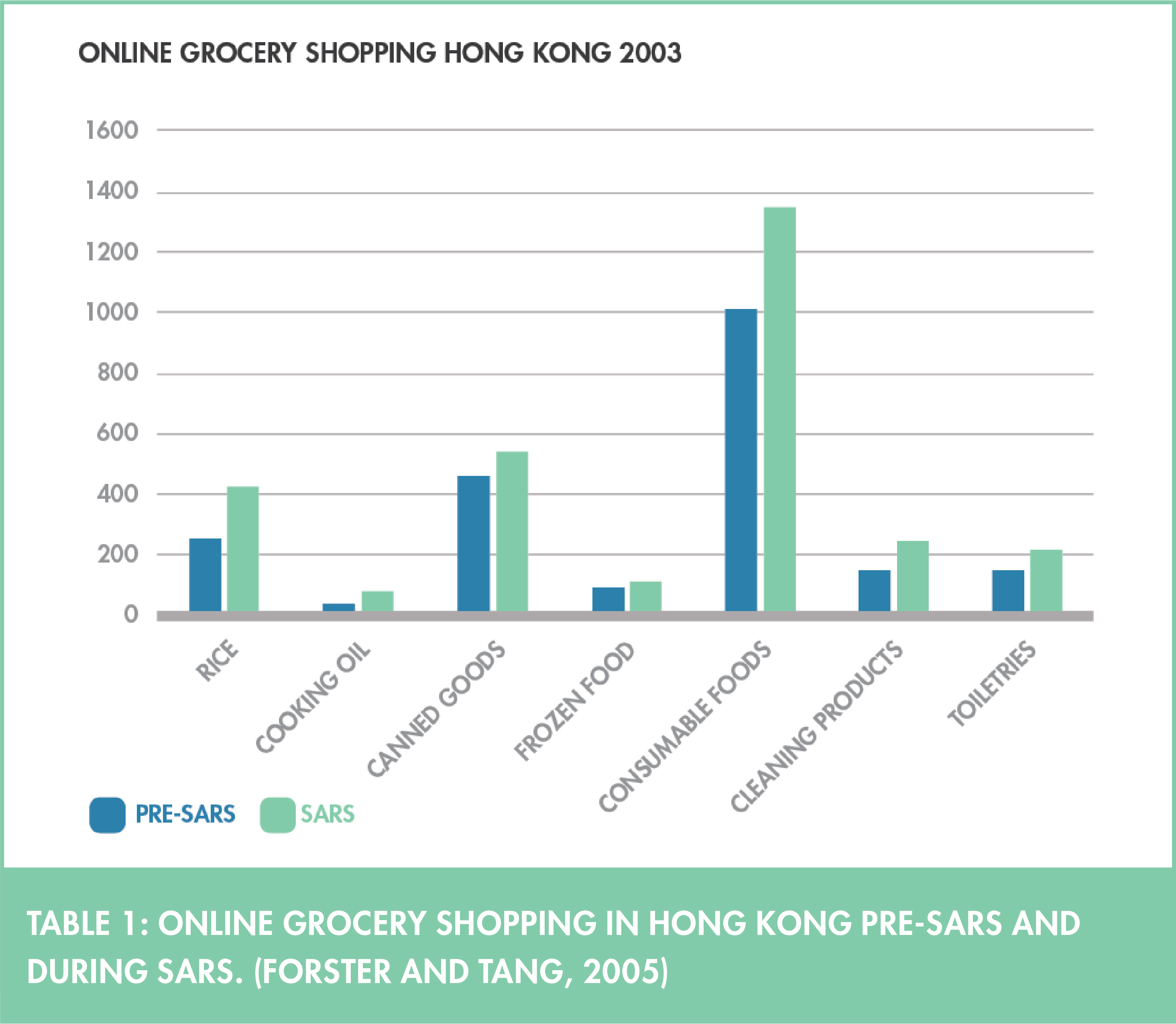

Another pattern that has become evident during the crisis is the growth of online buying. This pattern was also found in the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong, where studies showed that consumers increasingly bought their goods through online channels during the epidemic. Compared to levels before the epidemic, online sales of rice increased by 68%, cooking oil by 91%, canned goods by 18%, consumable foods by 33%, frozen foods by 20%, cleaning products by 68% and toiletries by 47% (please see table 1). The same study further showed that other online activities also increased during the outbreak. Similar increases have been observed during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Swedish Food Retail Index shows that online food retailing increased by 101% in April 2020. And although retails sales were pummeled overall, online Swedish fashion retail sales increased by 13% during the first quarter of 2020, according to the e-barometer report by the Swedish postal service. Internationally, similar increases in e-commerce have been reported. For instance, online retailing giant Amazon announced that they are hiring 100,000 new employees to cope with the increase in demand.

Whereas most research on consumer behavior during crises affirm the picture of individuals spending less (yet proportionally more on basic goods) and often buying in bulk through online channels, some research also reports deviations from this pattern. Individuals who acutely felt that they had lost control over their own fate during Hurricane Katrina, oftentimes individuals with lower incomes who experienced these feeling because of a lack of financial buffers, reported that they engaged more in impulsive and even compulsive buying behavior. This behavior was often a way to numb one’s feelings and restore control during episodes of severe stress. Despite these troubling findings, however, most consumers spend carefully, not only during crises but also immediately post-crisis.

Consumer behavior post crises

Experiencing a pandemic or a natural disaster, with all the stress and anxiety that is typically associated with it, often instills a sense of caution in the consumer. While some analysts predict that consumers will return to their pre-crisis consumption patterns quickly once coronavirus restrictions are lifted, the evidence from similar events suggests otherwise. Studies in the aftermath of hurricanes and wildfires in the U.S. suggest that feelings of uncertainty, fueled by financial hardship, lead consumers to also hold back on spending after a crisis. People who experienced such events told interviewers that they were much more deliberate with their purchases post-crisis. They were much more risk-averse and took their time buying new products. Other studies indicate that this might be due to a shift in what is considered important in life. Studies on consumers after of the attacks on 9/11 and in the aftermath of the SARS outbreak show that stressful situations that remind individuals of the fragility of life lead to an increased focus on emotional meaning rather than material benefits.

Add to this that we will only slowly exit this crisis in the wake of a big economic recession with increasing unemployment levels. This is likely to change consumer behaviors also in the longer-run. Previous research shows that reductions in spending during economic downturns are not only due to reductions in income. Even consumers who have resources available tend to consume less in difficult economic times. Economic crises lead to reduced and postponed consumer spending in general. This in turns contributes to the depth of the crisis. What is more, consumers tend to be less likely to explore new products and turn to low price and economic options. In the period following the financial crisis of 2008-2009, a big change in consumer behavior was the shift towards low-price alternatives and it is likely that this will continue to be the case as we exit the current crisis.

Stressful events such as recessions and crises typically also increase a consumer’s desire for simplicity to ease their cognitive load. This affects decisions as wide-ranging as design choices, brand preferences and even where people choose to live. Tumultuous events such as WWI gave rise to the Bauhaus school of design with its emphasis on ‘form follows function’, which eventually contributed to the rise of functionalism. In modern times, recessions have seen the rise of successful magazines such as Real Simple in 2000. Some researchers also suggest that the recession of the early noughties contributed to the success of the simple but functional iPod. Studies also indicate that consumers’ quest for simplicity after a crisis will affect their choice of brands. Serving partly as a bearer of information, brands tend to simplify consumer decision-making by serving as rules-of-thumb. Choosing strong and well-established brands could therefore be a way of reducing cognitive effort in a stressful situation following a crisis or a recession.

The desire for simplicity might also affect where people choose to live after the COVID-19 situation has subsided. Studies on migration show that crises and recessions shift migration patterns and the current pandemic has fueled speculations that workers, having seen their city life tainted by a lockdown and the spread of a deadly virus, might flee to the countryside in search of a simpler life, outdoor space and a sense of community. This would shift the demographics of many regions, with retailers in rural areas potentially gaining customers. The experiences of many white-collar employees of working from home, using digital solutions during the pandemic, might accelerate a shift towards remote working from rural areas.

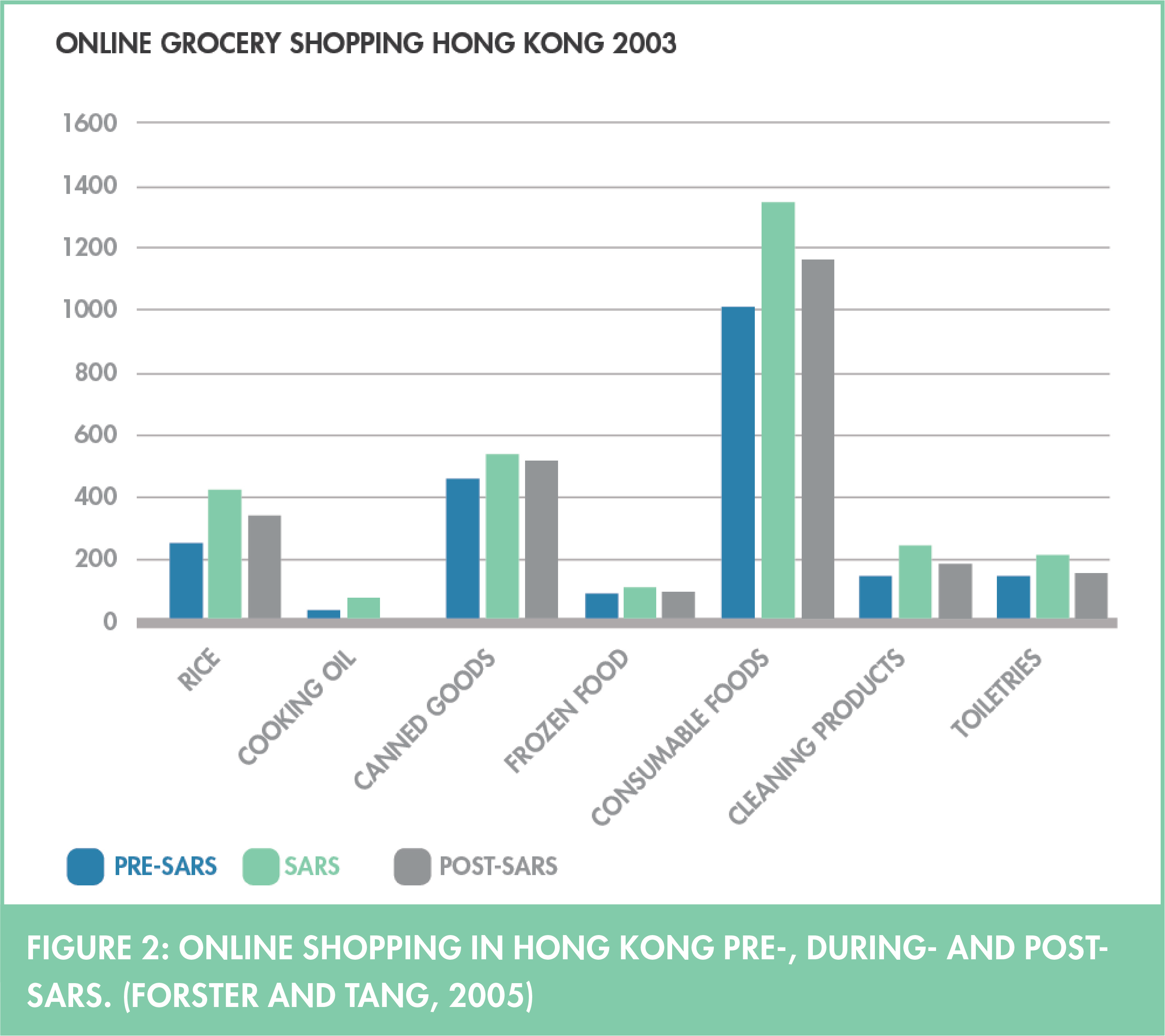

The crisis will also accelerate a shift towards even more online shopping. Analysts predict that the outbreak of the coronavirus will speed the shift to e-commerce. Forrester research, for instance, predict that by 2024, a third of non-grocery spending will be online and grocery retailing will have more than doubled its online share. In Sweden, we also see a big move towards online in the older age-groups, which have previously been less inclined to use this channel. The existing research from the 2003 SARS outbreak supports this prediction. Continuing to track online grocery sales after the outbreak, researchers concluded that for most of the categories surveyed, online sales levels after the epidemic exceeded those immediately prior to the outbreak. Compared to before the outbreak, online sales of rice increased by 33%, cooking oil by 38%, canned goods by 13%, consumable foods by 16%, cleaning products by 24% and toiletries by 3%. Only frozen foods decreased somewhat, by -4% (please see figure 2).

Consumer behavior might also shift due to structural changes imposed by governments during the current pandemic. Consumer behavior can shift either through individuals’ internal motivation or through forced changes imposed from above. One example is when smoking was outlawed in bars and restaurants, forcing a shift in smoking habits. In order for structural changes to succeed, these interventions must usually have some level of popular support to begin with. During the financial crisis of 2008-2009, for instance, widespread anger at bank practices and boardroom behavior paved the way for financial regulations in the U.S. During the COVID-19 outbreak, a debate has started to rage between those who want a return to consumption patterns seen before the pandemic and those who want states to force companies that receive government assistance to develop more sustainable business practices. These demands have been heard from activists and members of the general public, but also from within company ranks. Thus, popular support seems to exist at all levels of society. The possibility of such structural changes in response to pressing issues, like climate change, therefore exists. This might bring about changes in consumer behavior that might be more long-lasting than those resulting from the psychological effects of the crisis.

Opportunities for companies post crises

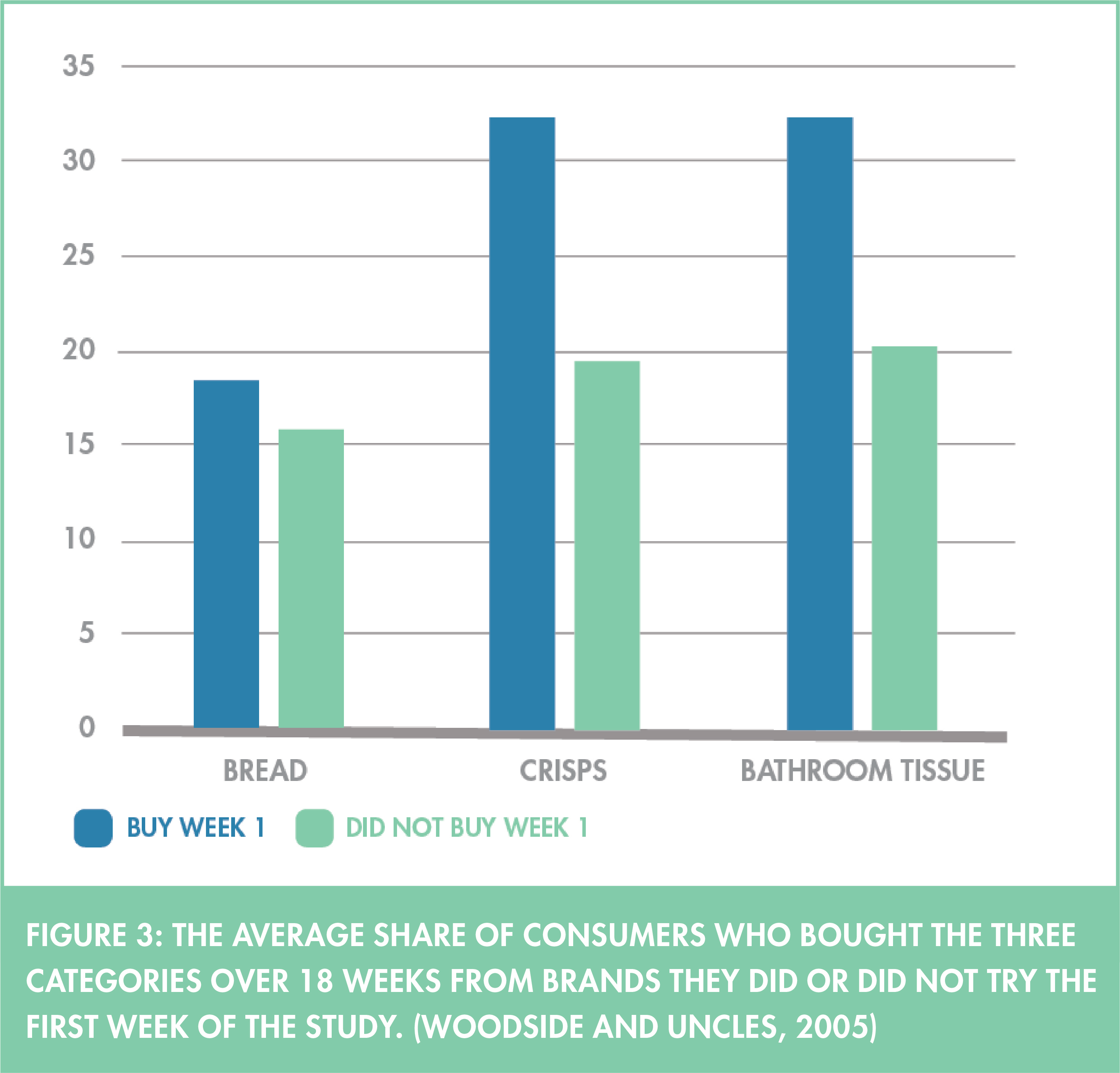

While many of the developments outlined above will spell trouble for companies the world over, there are also business opportunities that will arise from the current crisis. As our patterns for work and socialization change, so will our behavior as consumers. Many of us will face radically new situations both in our professional and personal lives once this crisis subsides. Research on consumer behavior shows that changes in life give rise to new purchasing patterns. Given the changes, consumers tend to find themselves in new buying situations and these help consumers form new buying habits. Interestingly, studies show that in such new situations, consumers often stick to the first brand they try in different categories, provided that the experience is satisfactory. This effect is referred to as behavioral primacy and was documented by researchers Arch G. Woodside and Mark D. Uncles in 2005. The researchers placed consumers in a new and unfamiliar purchasing situation where they had access to multiple brands in three different categories (bread, crisps and bathroom tissue) over a period of 18 weeks. The aggregate results show that if consumers bought a brand in the first week of the study, they were much more likely to choose that brand over the next 17 weeks (please see figure 3)

Woodside and Uncles speculated that consumers might behave in this way to reduce the cognitive effort associated with shopping. Simply put, since people have other things on their minds than shopping for seemingly mundane products, they do not have the energy to think too much about what brands they choose. If the first brand they try is satisfactory, they therefore tend to buy that brand more often rather than trying new ones.

As noted above, the current situation with COVID-19 and the changes that it will give rise to ought to generate feelings of uncertainty and stress in consumers. Thus, they should be especially prone to reducing the cognitive effort associated with shopping right now. In all the new purchasing situations that will occur as a result of the current crisis, a behavioral primacy effect could be expected. We therefore recommend brands and retailers to invest rather than cut back on marketing and promotions right now, as they might gain many new customers that could generate revenues for a long time. Given that other brands might cut back on marketing at the moment, reducing the advertising clutter and allowing for better reach of marketing messages, investing in marketing should be an all the more appealing strategy.

No-one knows what the future will hold. One thing that we can say for sure, however, is that the retail landscape will look different in a post-corona virus world. The competitive landscape, for example, will be forever altered given the wave of bankruptcies we have seen in the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis. That, along with the formation of new consumer habits outlined above should bring opportunities for those retailers left standing after the pandemic subsides. However, challenges will abound as well. The recession that seems certain to follow this pandemic will be one of them as consumers will be reluctant to shop in an uncertain economic environment. Shifting priorities towards emotional rather than material meaning might be another. An interesting development is the move towards more sustainable products and services, which has been growing in the past decade. Although consumer attitudes have not always been aligned with their behaviors in this regard, consumer desires for more sustainable lifestyles were growing before the pandemic. During the crisis, people have been given the opportunity to experience what less polluted cities and waterways look like during the lockdowns. This might lead them to raise their voices in order to keep their environment that way. Nevertheless, the economic downturn will also lead consumers to search for value, suggesting that companies need to find ways to make sustainable options economically viable for consumers if there is to be a more lasting change in consumer behaviors relate to sustainability. There is also an ongoing discussion of how governments might use the crisis to rethink our societies to make them more sustainable, which could lead to new regulations that force retailers to comply with these new directives. On the other hand, companies might not want to wait for these structural changes to occur. Satisfying customer demands, after all, is what retail is all about. A transition towards more sustainable business practices might therefore not just be good for the environment, but good for business too.

References

Forster, P. W. and Ya Tang, "The Role of Online Shopping and Fulfillment in the Hong Kong SARS Crisis," Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 2005, pp. 271a-271a, doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2005.615.

Wetter, E., S. Rosengren and F. Törn (2020), Private Sector Data for Understanding Public Behaviors in Crisis: The Case of COVID-19 in Sweden, SSE Working Paper Series in Business Administration, Stockholm School of Economics, No. 2020:1.

Woodside, A. G. and Mark D. Uncles, (2005) “How Behavioral Primacy Interacts with Short-Term Marketing Tactics to Influence Subsequent Long-Term Brand Choice,” The Journal of Advertising Research, 45 (2), 229-240.