Who benefitted from the gasoline tax cut in Sweden?

Against the background of fast rising gasoline and diesel prices in 2022, a number of European countries have reduced fuel tax rates, often in the form of temporary “gas tax holidays”. Sweden reduced its fuel tax rate by 1.81 SEK (€0.17) per litre on May 1st 2022, of which 1.31 SEK is a temporary reduction set to expire at the end of September. When the tax holiday was announced, Finance Minister Mikael Damberg commented “I am pragmatic, for me it is important that we can compensate households” (Davidsson and Nilsson, 2022). However, just one month after implementation, the pump price for gasoline rose to a new high, which gives rise to the question of how much of the tax cut has actually been passed through to the consumers.

In this policy brief, we analyse the tax incidence by comparing the gasoline price development in Sweden to that in Denmark, where the fuel tax rate remained unchanged. We find that the tax reduction was fully reflected in consumer prices, with a pass-through rate of around 100 percent. Nevertheless, we argue that spill-over effects pushing up gasoline prices outside of Sweden are likely biasing our estimate. Based on economic theory, we conclude that our estimate of the pass-through rate needs to be corrected downwards, meaning that only a part of the tax cut benefit was passed along to Swedish consumers.

Introduction to tax incidence

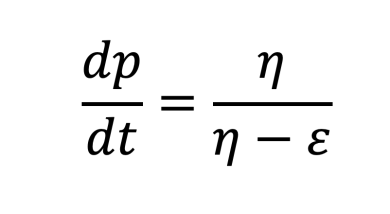

In standard economic theory, the pass-through rate to consumers from a change in gasoline tax rates is determined by the equation:

where p is the tax inclusive price, t is the tax, and η and ε are the price elasticities of supply and demand, respectively. The price elasticities give us the percentage change in quantity when the price changes by one percent. It follows from this equation that the relatively inelastic side of the market bears most of the tax burden from a tax increase – or most of the benefit from a tax reduction. Under normal circumstances short-run demand for gasoline is highly inelastic in Sweden, with ε close to zero (Gren and Tirkaso, 2020; Dahl, 2012). In contrast, short-run supply is considered relatively elastic due to the competitive nature of the industry. Thus, changes in gasoline tax rates in Sweden are usually passed through fully to the consumers (Andersson, 2019). This implies that consumers bear the entire burden in the case of a tax increase but reap all the benefits in the case of a tax reduction.

Using Denmark as a counterfactual

The problem is that existing price elasticity estimates – computed using historical price data – do not capture the temporary supply restrictions in the context of the war in Ukraine or the supply and demand shocks from the Covid-19 pandemic. In lack of reliable estimates of current price elasticities, we revert to analysing the tax incidence using a quasi-experimental and empirical approach. This requires a counterfactual – a comparison unit that captures the evolution of gasoline prices in Sweden had the tax cut never been implemented. Denmark is well suited for this purpose given that it is geographically close, socio-economically comparable, and has similar levels of gasoline tax rates as Sweden. More importantly, Denmark has not made any recent fuel tax rates changes.

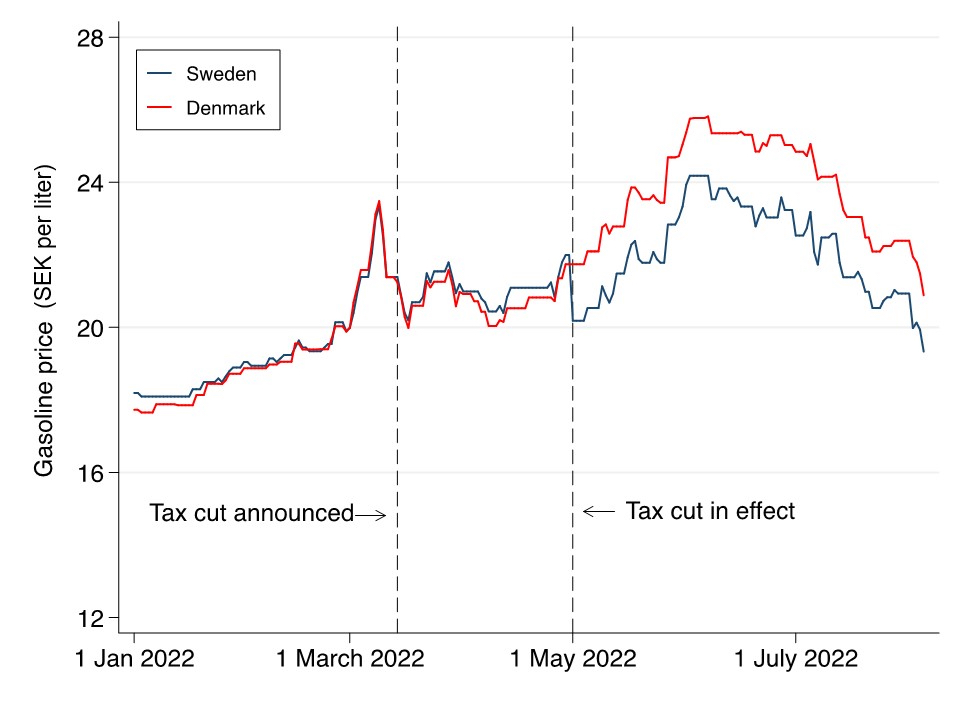

Figure 1. Gasoline pump price in 2022

Source: Gasoline prices in Sweden and Denmark are provided by CirkleK (2022). Daily exchange rates are provided by Riksbanken (2022).

Figure 1 shows that the gasoline price in Sweden and Denmark track each other closely, displaying parallel trends in the time period leading up to the announcement of the tax cut on March 14. This reassures us that Denmark is a credible comparison unit for Sweden. Gasoline prices start diverging in the interim period of around 7 weeks between the announcement and the implementation of the policy. The fact that the gasoline price in Sweden is slightly higher during this period than in Denmark provides some speculative evidence that suppliers in Sweden intentionally raised prices in anticipation of the tax cut, allowing them to capture parts of the benefit. As soon as the tax cut enters into effect, the gasoline price is notably lower in Sweden compared to Denmark, although prices continue to rise until June.

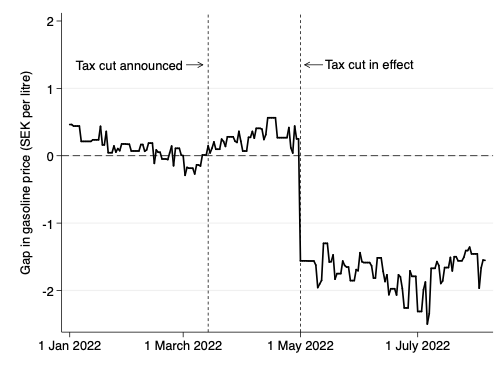

Figure 2. Gap plot of price difference

Note: The figure plots the difference between the Swedish and Danish gasoline prices from Figure 1.

It can be observed graphically from the gap plot in Figure 2 that most of the tax cut of 1.81 SEK was immediately passed through to Swedish consumers on May 1. Furthermore, there are no obvious signs of the effect wearing off over time; the pass-through rate remains fairly constant over the three months following the tax cut.

In order to obtain estimates of the pass-through rate, we run a simple difference-in-differences regression – comparing the average difference in gasoline price between Sweden and Denmark both before and after the tax cut. The price reduction after the introduction of the tax holiday is estimated at -1.89 SEK per litre compared to the price level before the introduction. This estimate is statistically significant and indicates a pass-through rate slightly above 100 percent. But since the price development in the interim period raises concerns about strategic price setting, it appears more appropriate to use the price level before the announcement as a baseline. By doing that, we find a relative reduction in the Swedish gasoline price of -1.82 SEK per litre, matching the size of the tax cut almost exactly, with a pass-through rate of 101 percent.

The estimated pass-through rate is biased

Our finding is in line with recent work on the German counterpart – known as the “Tankrabatt“. On June 1st 2022, the German Government lowered taxes on fuels for a duration of three months, amounting to a total tax relief of around 35 cent for gasoline and 17 cent for diesel, respectively. A number of studies find a full or close to full pass-through rate from the Tankrabatt, with estimates ranging between 85 and 102 percent (Fuest et al., 2022; Dovern et al., 2022; Montag and Schnitzer, 2022). Analogous to our approach, these studies rely on a comparison with a counterfactual unit, either France or a weighted average of Germany’s neighbouring countries.

Yet, by focusing on the pass-through rate at the national level only, we risk not capturing the full tax incidence. The supply of gasoline is more inelastic at the EU level than at the national level. As Sweden cuts the tax on gasoline, the after-tax price falls and this leads to an increase in demand; supply adjusts as more gasoline comes in from neighbouring countries. At the aggregate level however, supply is more constrained, so the tax cut in Sweden results in a marginal increase in gasoline prices across countries in the EU. This marginal increase in prices amplifies as more countries implement their own tax cuts. Indeed, Sweden and Germany are not the only countries to have implemented tax cuts in response to increasing oil prices, but are part of a larger group of countries to have done so, including Belgium, Italy and Poland (Sgaravatti, Tagliapietra, and Zachmann, 2022).

The spill-over effect from the tax cuts onto gasoline prices in “untreated” countries has two important implications for our analysis. First, our estimated pass-through rate to consumers in Sweden is biased upwards. The gasoline price development in Denmark can only act as a credible counterfactual for that in Sweden in the absence of the tax cut provided that it is not affected by the tax cut itself. But this condition is not fulfilled as the tax cuts employed in Sweden and elsewhere can be suspected to have led the gasoline price in Denmark to increase more than it would have otherwise. Estimates of pass-through rates near 100 percent thus appear overstated and consumers likely benefit less from the tax relief in reality. Second, the benefit to consumers in countries that implement gasoline tax cuts comes at the expense of consumers in countries without such measures in place. An analysis of tax incidence at the national level may find that most of the benefit from the tax cut is captured by consumers, whereas an analysis at the EU level as a whole would instead find that a much larger share of the benefit is actually captured by the supply side – in and outside of Sweden. This demonstrates that the national incidence of the tax cut is different from an international one.

The Swedish tax cut benefits producers and richer households

The prevalence of spill-over effects makes it difficult to conduct causal inference analysis and estimate the true effect of transport fuel tax cuts empirically. Still, the previously outlined theoretical framework on tax incidence can help provide valuable insights. As discussed, gasoline demand is much more inelastic than supply in normal times, so we could expect the tax cut to be passed through to consumers at fairly high rates. However, gasoline supply today is likely more inelastic than usual in light of the repercussions from the economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine: with oil companies unable to ramp up production in the short term because of underinvestment into existing and new fields during the pandemic (Ashraf et al., 2022). In Europe, Russia accounts for more than 20 percent of the oil supply but production in Russia has gone down since the launch of the war in Ukraine. Many European companies had started to engage in self-sanctioning by cutting ties with the Russian energy sector even before the European Council agreed to embargo most oil imports from Russia by the end of the year 2022 (Adolfsen et al., 2022). Furthermore, the refining industry is facing capacity constraints due to shutdowns that took place in the course of the Covid-19 pandemic as well as high prices for gas powering its operations. All of these factors together illustrate why gasoline supply at the EU level has become more inelastic in the past weeks and months. As a consequence, the relative elasticity of gasoline supply and demand is distorted towards benefitting the producers more than usual. Hence, we can infer from economic theory that not all of the benefit from the gasoline tax cut went to Swedish consumers, but that producers in Sweden and abroad captured some of it.

Apart from this, the tax cut does not benefit all households equally. Among the 20 percent of households with the lowest disposable income in Sweden, only about half have a direct expenditure on transport fuel. But among the 20 percent richest households, around 95 percent have positive transport fuel expenditures (Statistics Sweden, 2020). A cut in transport fuel tax rates therefore disproportionately benefits high-income households in Sweden.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that the transport fuel tax cuts employed in various countries do not come without a price tag – they represent a cost to the state budget and ultimately its citizens in the form of foregone tax revenues. In the case of Sweden, this amounts to 6.2 billion SEK in 2022, or around $60 per person (Swedish Government, 2022; Ministry of Finance, 2022). A broader evaluation of the welfare effect of the tax cut needs to take into consideration what the tax revenue would have been spent on had the tax cut not been implemented.

Conclusion

In mid-August, a report published by Konjunkturinstitutet (National Institute of Economic Research) stirred up the public debate on the gasoline tax holiday in Sweden. According to their report, considering what they call a notification and a pick-up effect (Konjunkturinstitutet, 2022), only 62 percent of the tax reduction on gasoline was passed on to Swedish consumers. The authors claim that sellers of gasoline exploited their market power through charging higher prices in the weeks leading up to the introduction of the tax reduction – the notification effect – and again shortly after the introduction – the pick-up effect. In this policy brief, we obtain a considerably higher estimate of the pass through rate of around 100 percent. In addition, we only find evidence for a weak notification effect and do not share the view that a pick-up effect has taken place. Even though our studies have in common that we consider Denmark as a counterfactual, we see several advantages in our empirical methodology that may explain the different results: The data we use for both Sweden and Denmark come from the same gasoline company, which improves comparability of prices. The time period we study after the tax cut covers three months instead of only one, and our finding is robust to the inclusion of a time trend, whereas the main results in the report by Konjunkturinstitutet (2022) rely heavily on the addition of such variable in their model.

What we would like to emphasise in the present case is that any methodology based on counterfactuals is prone to bias. If you shift the level of analysis from a single country in isolation to the whole of the European Union, it becomes clear that the Swedish gasoline tax cut brings about a marginal increase in gasoline prices outside of Sweden. This is why our estimates are likely biased upwards, revealing a flaw in both this study and the report by Konjunkturinstitutet (2022). In order to pin down the true pass-through rate to a precise number, a more comprehensive analysis is needed, although this may prove difficult. Without reliable empirical results, we should trust economic theory until now. The conclusions we can already draw are the following: Firstly, some of the benefit from the tax reduction is passed through to Swedish consumers but a full pass-through is an overstatement. It is important to note that even if gasoline companies only capture a small percentage of the benefit, this can still amount to large profits in absolute terms. Secondly, the gain from the tax reduction in Sweden produces losses to consumers in countries that have not lowered their tax rates. Thirdly, the policy favours high-income groups as the gains are not distributed equally among consumers within Sweden. Lastly, the corresponding loss in government revenue could potentially reduce welfare where expenditure is cut.

At the bottom line, the above economic reasoning suggests that the pass-through of the gasoline tax reduction to Swedish consumers is limited. And while we arrive at a similar conclusion as the report by Konjunkturinstitutet (2022), we follow a different line of argument. In our view, the reason for the imperfect pass-through to consumers does not necessarily lie exclusively in strategic price setting on the part of gasoline companies, but in the dynamics of the global market.

References

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in events, policy briefs, working papers and other publications are those of the authors and/or speakers; they do not necessarily reflect those of SITE, the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Photo by Deemerwha studio, Shutterstock.com