Green Growth? Sweden’s Carbon Policy Boosted Productivity in Trucking, Study Finds

Nov. 20, 2025

Sweden’s push to tax and regulate fossil fuels has long been held up as a test of whether climate policy can coexist with economic growth. An ongoing study of the country’s trucking industry, one of Europe’s biggest sources of transport emissions, suggests the answer may be yes.

Sweden’s ambitious climate policies sent diesel prices soaring over the past decade, and instead of crippling the trucking sector, the pressure pushed its biggest players to become cleaner, more efficient and even more profitable, a new study shows.

Tracking more than 30,000 heavy trucks between 2007 and 2020, Swedish House of Finance researchers Gustav Martinsson (Stockholm University), Per Strömberg (Stockholm School of Economics) and Christian Thomann (KTH) examine how rising fuel costs shaped one of the economy’s most emissions-intensive sectors.

With carbon taxes climbing and biofuel blending mandates surpassing 25% by 2018, Sweden ended up with the highest diesel prices in the European Union. That created what the authors call a natural experiment: a rare chance to see how firms behave when emitting carbon becomes steadily more expensive.

“The Swedish trucking industry was able to lower CO₂ emissions by 5% while increasing output by 23%,” the study shows.

Policy, Not Oil Prices, Raised Costs and Drove Change

A key finding is that domestic policy, not swings in global crude prices, was the main force behind rising diesel prices.

“The climate policy component is up by over 60% and is the main contributor behind the rise in Swedish diesel prices during 2007–2020,” the authors note.

Bigger Fleets, Smarter Networks

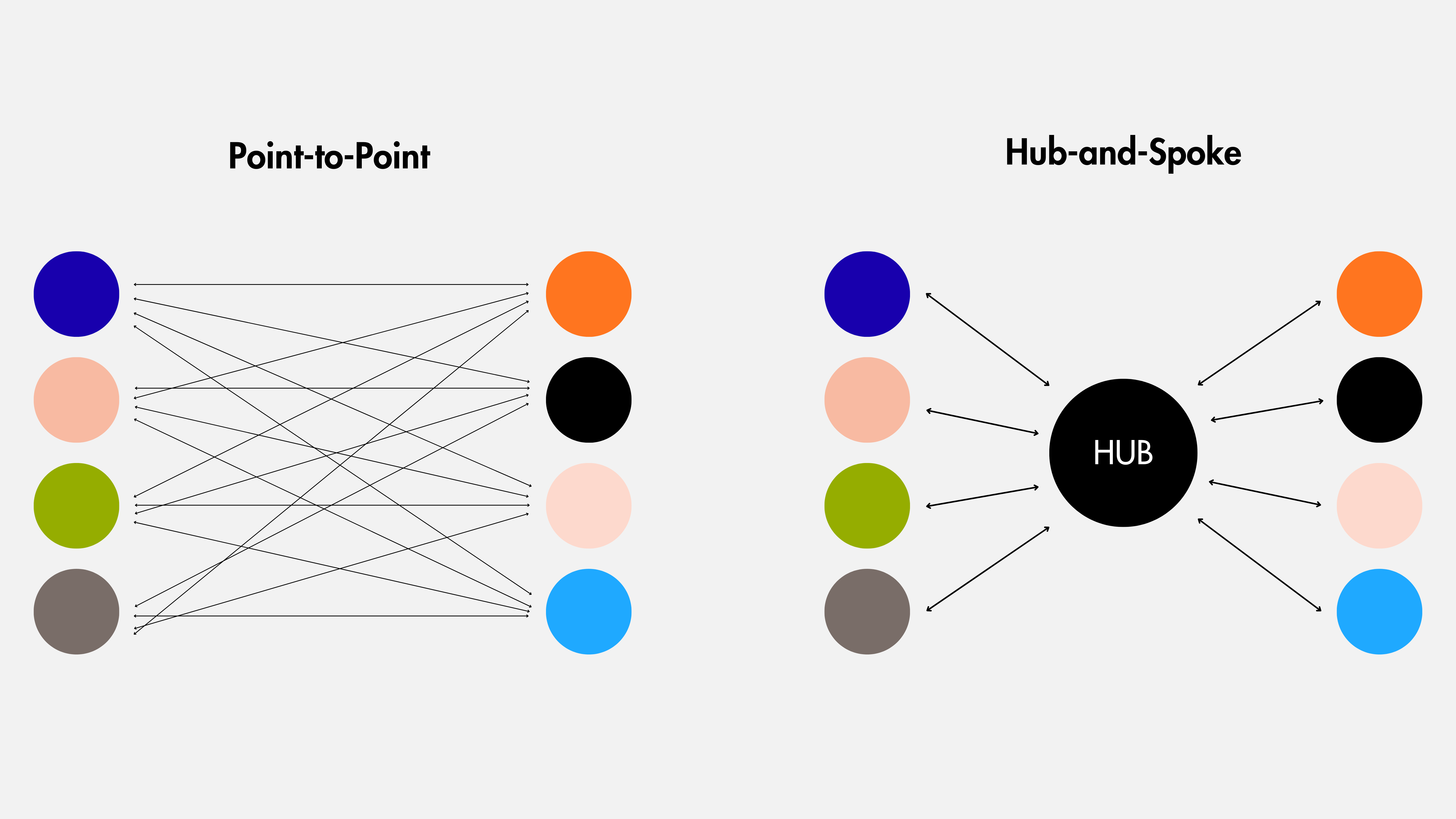

Facing higher fuel costs, large haulers invested in logistics and reorganized their networks. The study links efficiency gains to a shift toward hub and spoke distribution. Freight is first consolidated at central terminals, or hubs, before being moved along shorter delivery legs, the spokes. Heavy trucks handle long-haul links between hubs, while lighter vehicles handle local drops.

This marks a break from the older point-to-point system where partially filled trucks drove directly from sender to receiver along inefficient routes. As fuel costs increased, large operators “run shorter distances with a fuller load,” the authors find. Heavy-truck kilometers traveled fell, while lighter-truck activity increased in a pattern consistent with hub and spoke networks.

These logistics improvements require capital, software and network density. The authors note that such investments “exhibit economies of scale,” which helps explain why small firms rarely adopted them.

Winners and Losers

Large firms adapted and strengthened their competitive position. They increased output per truck, improved margins and cut emissions. Smaller firms changed little and lost market share. Operators with fewer than ten trucks lost eleven percentage points, while fleets with fifty or more than doubled in size.

Elasticity estimates highlight the divide. For the largest fleets, a one percent increase in fuel cost improved productivity by between 0.6 % and 1.5 % and reduced CO2 intensity by between 0.3 % and 0.8 %.

A Case of ‘Green Growth’?

Sweden’s experience shows how climate policy can reshape even hard-to-decarbonize industries. Rather than shrinking the sector, higher carbon costs pushed its biggest players to reinvent and improve their operations.

“Carbon pricing and biofuel mandates can achieve emission reductions in transportation without reducing productive efficiency and even help to increase it,” the authors conclude.