E-Bikes subsidies reduce reliance on cars and cut emissions, but at what cost?

Sep. 27, 2022

Are e-bike subsidies to reduce carbon emissions worth the cost? SHoF’s Anders Anderson and Columbia University’s Harrison Hong look into the welfare implications of the Nordic country’s e-bike subsidies in a working paper.

Transportation is the largest contributor to global warming and countries around the world are looking into tax rebates and discounts to spur green consumption and reduce emissions.

To mitigate the industry’s impact on the climate, Sweden introduced a SEK 1 billion (around USD 90 million today) subsidy program for electric bicycles (e-bikes) in 2018, which allowed buyers to receive a 25% subsidy on the retail price of a new e-bike, capped at 10,000 SEK (around USD 900).

It worked: e-bike sales nearly doubled; daily car commuting was reduced, while emissions from the consumers fell. Yet, after exceeding its per-year spending limit already during the first year, the program was axed.

Was the cost of the program worth the lower emissions? How much of the subsidy translated into higher prices versus higher quantities sold? Would the new owners have bought their e-bike even without the subsidy?

Sales of e-bikes surged, with little impact on price

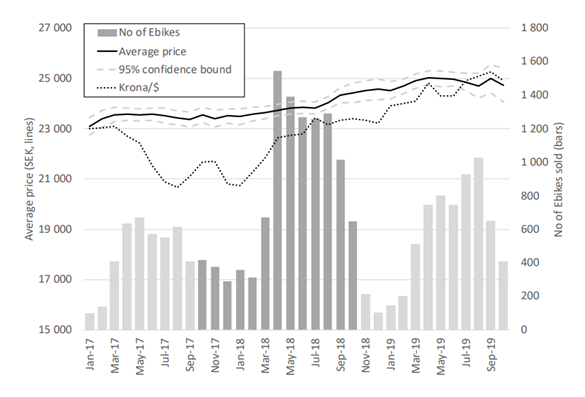

FIG. 1 displays the number of sold E-bikes of the top selling 38 models sold through the largest 49 retailers during the sample period. Dark grey shaded bars indicate the subsidy period October 2017 to October 2018 (right scale). The solid line displays average price which is recovered from the pass-through regression in Table II (left scale) along with a 95% confidence interval indicated by dashed lines. There are 20,586 observations in total during January 2017 to October 2019. The dotted line shows the Krona per dollar exchange rate which is normalized with the average bike price in January 2017. The data is obtained by matching paid out subsidies to sales data from Sweden’s largest insurer of e-bikes, Solid.

Sales of e-bikes surged during the subsidy program period. Aggregate data from the Swedish Bike Association suggest that 103,000 e-bikes were sold in 2018 when the subsidy was introduced, compared to 67,000 the year earlier.

To explore this general development in greater detail, Anderson and Hong matched the data from the Swedish Environment Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) showing e-bike purchases that received the subsidy with a sample of e-bikes sales obtained from Sweden’s largest insurer of e-bikes, Solid. This allowed for a detailed analysis of both volumes and prices of different e-bike models.

Figure 1 plots the sales and average prices for the 38 top selling models and shows no indication that sellers raised their prices during the subsidy period. Volumes during this period were up around 70% compared to the pre-subsidy period but did not fall back to pre-subsidy levels implying that demand kept on growing without the subsidy in place.

This showed that consumers of the e-bike did in fact receive the bulk of the subsidy and that the increased demand did not cause any notable increases in the e-bike prices that would counteract the purpose of the given discount. This is important since the objective of the subsidy is to increase the quantity of e-bikes sold.

A minority of new e-bike owners also owned cars

The main idea of using subsidies to foster green adoption is to attract “additional” consumers, that is consumers who would not have bought the e-bike without the subsidy.

The problem is that policymakers cannot easily distinguish these consumers from those who would have bought the e-bike anyway – the “non-additional”. This counterfactual is hard to disentangle.

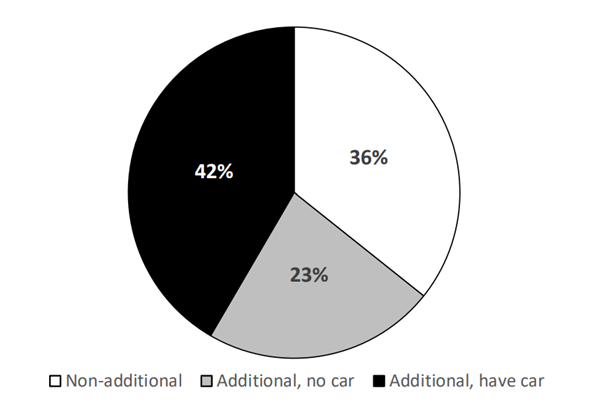

FIG. 2 shows the fraction of the 1,873 survey respondents classified as being non-additional or additional. Additional users are broken up into car owners and non-car owners.

But by using a survey commissioned by Naturvårdsverket, Anderson and Hong found that two-thirds of new e-bike owners viewed the subsidy as “important” in their decision to purchase in e-bikes, suggesting that majority of the consumers who took up on the subsidy were additional users or users who bought the e-bike because of the subsidy.

Although most of the respondents were additional users, only 42% of them were also car owners. 23% of the new e-bike users were additional non-car users while the remaining respondents were buyers who would have bought an e-bike regardless of the subsidy.

E-bike ownership led to less reliance on cars

E-bike ownership significantly reduced the owners’ reliance on cars for their daily commute.

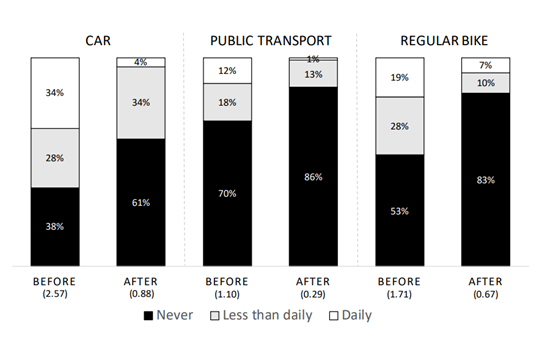

FIG. 3 displays the fraction of respondents indicating that they use a car, public transportation, or a regular bike daily (five days per week or more), less than daily or never for commuting before versus after the purchase of an E-bike. The average number of days per week used by each means of transportation is printed in parenthesis at the bottom of the bars. All responses are for transportation during summertime only. There are 1,873 observations in sample.

Before owning an e-bike, the mean days of car use for a single user was 2.57 days a week, and this more than halved after buying an e-bike, Anderson and Hong’s study showed. The frequency of daily car commuting also plummeted from 34% to just 4%.

Daily public transport commuting also significantly reduced, from 12% before e-bike purchase to just 1% after.

Meanwhile, regular bike commuting-- or the use of bikes without batteries-- also fell, although the fall was less severe than other forms of transportation.

E-bike use leads to emissions reduction, but at what cost?

To find out the subsidy’s efficiency to reduce emissions, Anderson and Hong weighed the cost of the subsidy against the social cost of carbon, or the price of the damage resulting from emitting one ton of carbon dioxide.

The true social cost of carbon is unknown but is estimated in various studies to be around USD 100 per ton. Another benchmark are the European carbon permits which have been trading in the range of USD 70 to USD 100 per ton recently. In this study, the authors asses what the social cost of carbon needed to be in order to justify the intervention.

By making assumptions on the lifespan of an e-bike, the study found that the total net carbon reduction of an e-bike was 1.3 tons. The average cost of the subsidy for each “additional” e-bike meanwhile, was USD 766.

By comparing this cost to the benefit of carbon reduction, the study found that the program could have broken even only if the social cost of carbon was USD 600 a ton. Therefore, the program cannot be justified on the basis of reducing carbon emissions alone.

E-bike subsidies around the world

Countries around the world are looking into incentives like subsidies to increase green consumption and reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

As of the end of 2021, there were more than 300 tax-incentive and purchase-premium schemes for cycling offered by national, regional, and local authorities across Europe, European Cyclists’ Federation data showed. While many incentives in Europe were already introduced in the last decade, the number of schemes has increased significantly since 2019.

The U.S. introduced an e-bike bill that offers a 30% tax credit for E-bike purchases earlier this year, and there are already many regional incentives in place across the country.

The Green Party in Germany meanwhile, proposed to promote the purchase of cargo bicycles, with subsidies totalling up to 1 billion Euros.

A capped discount targeted directly towards consumers, like in Sweden, is by far the most popular type of intervention, followed by tax credits and flat rates that are sometimes also combined with scrapping a fossil fuel vehicle, known as a “Cash-for-Clunkers” program.