Hedging EU’s “winter risk” by curbing gas demand: Solidarity, nudge, and market solutions

The concern of Russian gas supply disruption and its implications has never been as serious. Experts agree that supply-side measures would not be enough to cover the shortage. Demand cuts are needed. The EC has just proposed a solidarity-based plan of 15% gas demand reduction across the EU Member states. However, getting all EU countries to commit to this plan has been challenging due to asymmetries in their exposure to the Russian gas crisis.

As a result, the EU approved a compromise plan with numerous exemptions. This brief argues that market-based solutions may improve participation incentives helping the EU to coordinate decreasing gas demand. Nudging energy consumers to lower their demand may be an efficient complementary solution. All member states should adopt this latter strategy now, as it takes time to trigger behavior changes in energy consumption. Acting now should strengthen resilience in the coming winter.

Background

Since the beginning of the conflict between Ukraine and Russia, both politicians and analysts have expressed concerns about cuts in Russian gas supply and their implications for the European economy. These concerns have only deepened as the crisis has unfolded. First, Russia stopped gas deliveries to five EU member states in April 2022 following their refusal to pay for gas in rubles. Then, Gazprom cut the capacity of the NordStream pipeline, initially by 40% and then by another 20% in June 2022, claiming technical problems originating from sanctions (i.e., a sanction-driven late return of a gas turbine repaired in Canada).

Gazprom’s July 18th announcement of its inability to deliver contracted gas amounts due to “force majeure” further added to the concern. Meanwhile the EU has dismissed the alleged technical failure stressing political reasons. According to EC President Ursula von der Leyen, the delivery stop reflects a “use of energy as a weapon”.

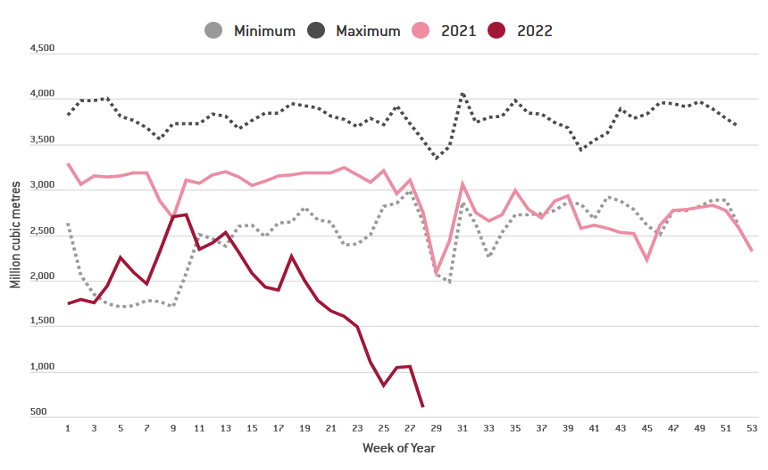

The panic somewhat settled on July 21, 2022, when Russian gas shipments via Nord Stream resumed at 40% of its original capacity, i.e., the mid-June level. However, Gazprom just announced another cut to 20% of the original capacity from July 27th. Overall, Russian gas exports to the EU are unprecedently low, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Russian gas exports 2021 vs. 2022

Source: McWilliams, B., G. Sgaravatti, G. Zachmann (2021) ‘European natural gas imports’, Bruegel Dataset, based on Entsog

Whether Russian gas supplies are likely to be stopped completely in a very close future is unclear. In similar vein, the IEA Executive Director, Dr Fatih Birol, warns that “…it would be unwise to exclude the possibility that Russia could decide to forgo the revenue it gets from exporting gas to Europe in order to gain political leverage”. Regardless of this risk, large-scale adjustments are necessary even under the more optimistic scenario with Russian gas supplies kept at the current level.

The most direct way to tackle the shortage of Russian gas is from the supply side. It can be done via three main channels: diversification of gas suppliers, replacement by alternative fuels, or use of storage. Multiple sources have studied these options extensively (see, e.g., SITE (2022) for an overview of earlier assessments, as well as Di Bella et al. (2022) for more recent estimates and a literature overview). Despite different shortage estimates across reports, experts agree that supply adjustment will not be enough to compensate for ‘the missing Russian gas. This suggests that curbing demand will be a substantial part of gas crisis management.

Most of the demand-linked measures decided by the EU member states have been to counteract the sky-rocking gas prices and subsidize gas consumption by setting a price cap or providing an energy check (see von der Fehr et al. 2022 for an overview). While such measures may protect consumers against increased energy bills in the short run, they foster energy consumption rather than curb it. However, on July 20th, the European Commission issued a plan for the EU nations to cut their gas consumption by 15% between August 2022 and March 2023. This move is part of a wider EU strategy to respond to the gas crisis by pushing for a solidarity mechanism between the member states, including pooling (i.e., sharing) of economic losses. While the targets in this plan would be voluntary, the restrictions could become binding in an emergency. The main demand restrictions would apply to the industrial consumers, but countries are also expected to facilitate households’ demand adjustments. This plan faced resistance from a range of EU Member states, claiming unfairness of 15% cut for their countries, or objecting binding demand cuts for their countries. The resulting compromise agreement, accepted by the EU states on July 26th, incorporated numerous exemptions for both countries and industries.

This brief focuses on the current options in the EU to curb energy demand. We discuss the feasibility of a solidarity mechanism in this context and offer economic mechanisms that may improve its functionality. We also stress the important policy features in incentivizing consumer response.

Solidarity rule and market mechanism

Solidarity and coordination between Member states constitute a crucial part of EU’s response to the current gas crisis. Implementing these rules would limit the direct (gas shortage) and indirect (price-driven) shocks through, e.g., mutual backing-up and buyer power (see, e.g., Le Coq and Paltseva, 2012, 2022 or IEA, 2022).

The solidarity approach was discussed long before the current gas crisis, at least since 2006 (EC, 2006). However, its implementation has proven challenging because of the energy-related asymmetries between Member states in terms of import dependency, diversification of suppliers, energy portfolio, etc. These asymmetries undermine a “one size fits all” policy approach and make some countries consistently benefit more from solidarity mechanisms than others. The solidarity mechanism may also create moral hazard problems (Le Coq and Paltseva, 2008). As a result, the EU could never fully adopt a common energy policy approach.

The recent EU call to cut energy demand by 15% is subject to the same shortcomings. The EU countries are unequally affected by the current gas crisis due to differences in their exposure to Russian gas, access to storage or alternative fuels, gas transportation bottlenecks, etc. These differences undermine countries’ willingness to coordinate as witnessed by Portugal’s and Spain’s explicit opposition to the call on the ground that their energy reduction would be unfair given their energy portfolio with almost no Russian gas. Poland, whose gas storage is full, and Hungary, whose government imposed an export ban on gas earlier in July, have also objected the deal.

There are several ways to improve coordination: one could provide part-taking incentives via a monetary transfer scheme, incorporate demand-side energy cuts into a larger political agenda so that the (asymmetric) losses in one area are compensated by gains in another one (Le Coq and Paltseva, 2008). However, both solutions are likely unfeasible in the current, relatively short-run context, as they require the collection of large volumes of information to determine the correct transfer size. Additionally, the incentives for EU countries to correctly report such details might be low. One can also design a mutual support scheme with country-specific participation requirements/exemptions. This solution, while also informationally demanding, may be easier to achieve. It is likely to improve participation incentives, but the effects of solidarity may be weaker than under a plan without exemptions.

The EU decided to follow this latter route: On July 26th, the EU managed to reach an agreement on a softer plan with multiple exemptions from the 15% cut, accounting for countries’ energy market asymmetries (as well as much more demanding procedure to make the demand cut binding). While this agreement is definitely a step forward, it is currently uncertain whether it would be sufficient to meet the gas demand challenges in the coming winter.

A number of market solutions can potentially improve on the situation. For example, one could establish a market for energy demand reduction quotas in line with the cap-and-trade program designed for CO2 emissions. Alternatively, an emergency gas auction (like the one discussed in Germany for industrial firms) could allow gas savings to be offered in an auction. The winning, cheapest bid would get a market-price level compensation. Of course, such market mechanisms are likely to imply (at least some) consumers will face surging gas prices, but this appears inevitable in view of the difficulties to implement rationing mechanisms to cope with the reduced gas supply.

Market solutions could also be implemented at member state level. However, such an implementation would likely limit solidarity between member states and increase the costs associated with reduced gas consumption. Indeed, purely national solutions (almost by definition) lack solidarity mechanisms between member states and in addition inhibit that the gas reductions take place where they are the least costly.

Nudging and information campaign

Given the gas crisis and implementation frictions, the EU should benefit from complementing the regulatory and market solutions (mainly targeting the industry) by incentivizing the demand-cutting behavior of private consumers. There are many ways to trigger behavioral change, from changing legislation to nudging consumers to persuade them to lower their gas (and energy) consumption. Some nudging policies have been successful in the past. One example is Japan’s “setsuden” (electricity-saving) campaign, run after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear plant disaster. It started as an unofficial movement and continued into regulatory restrictions for large firms and voluntary but highly encouraged household targets. The information campaign stressed how close the country was to blackout and successfully prevented blackouts.

In the current crisis the EU states’ policies towards consumers were concentrating on shielding them from high energy prices (see von der Fehr et al, 2022 for an overview). Nudging and energy-saving information campaigns in the EU are yet to gain momentum. Some of the larger EU members are leading the movement. For example, in France, the president called for an immediate “energy sobriety” on the last National Day. Businesses and public buildings were asked to switch off the light at night and anticipate a lower winter heating consumption. While fines for infringement are under discussion, the French government is hoping for a nudging effect. Similarly, Germany has started an intense information campaign to convince individuals to reduce their electricity consumption by taking fewer showers and turning down the air conditioning. However, much broader, intensive energy-saving campaigning is urgently needed to lower energy demand effectively.

Several results from the experimental economic literature motivate such campaigns. The first point concerns the usefulness of nudging in the energy context. The evidence on the effect of incentivizing consumers’ energy saving behavior via monetary or non-monetary interventions is mixed (see Andor and Fels, 2018 and Lingyun Mi et al., 2022 for an overview). However, a recent meta-study combining the results from 112 field trials between 1976 and 2021 (Lingyun Mi et al., 2022) supports the effectiveness of non-monetary incentives (such as nudging by providing information or offering social comparisons) in creating energy-saving behavior. Moreover, it finds that non-monetary incentives are also more effective and longer lasting in promoting energy conservation than the monetary ones. One possible reason for this finding is that non-monetary incentives may affect individual’s values and their intrinsic motivation to save energy. This result implies that information campaigns, target-setting, and providing social comparisons can be an effective and relatively cost-efficient way to lower energy demand.

The second question concerns the timing of such intervention. Again, while there is no clear-cut evidence concerning the long-term impact of nudging, some literature documents effects lasting months and even years after the intervention stopped (Andor and Fels, 2018 overview a few such studies). Further, the same meta-study by Lingyun Mi et al., 2022 found that interventions lasting 1–6 months were the most effective. A combination of antecedent (before actual behavior, such as goal setting) and consequence (when the incentives to act are affected by the results of the action) nudge-based interventions produced the best energy-saving effect. These findings suggest that campaigns should start now to be ready for the winter 2022-23 season.

Last but not least, there is evidence that energy conservation goal-setting is effective only when the goals are realistic. For example, in Harding and Hsiaw (2014), a moderate energy saving goal set by a household led to a sizable consumption reduction, and the effect lasted for one and a half years. With more ambitious goals the initial strong response quickly vanished. Finally, there is no consumption adjustment pattern with unrealistically high goals. One possible, even if somewhat stretched, interpretation of these results could be that a drastic change in consumption may be more challenging to incentivize through nudging than a series of more minor adjustments. This consideration provides another rationale for the early start of nudging policies, suggesting a meager initial consumption reduction, and gradually increasing the threshold.

Conclusion

Cutbacks in gas consumption are essential to surviving the EU energy crisis, especially in case of a complete Russian gas halt. The EC has recently proposed a plan for the EU nations to decrease their gas consumption by 15% between August 2022 and March 2023. This plan is included in a wider solidarity approach to EU energy crisis management. However, approval of this plan by the EU nations faced difficulties due to asymmetries in exposure to Russian gas across EU member states and the resulting unwillingness to share the costs of the crisis. The resulting compromise plan features multiple exemptions from the 15% rule. Market solutions, such as trade in demand reduction quotas, may help to improve EU coordination on demand reduction. Another essential component of crisis management is the EU-wide nudging of private consumers encouraging energy saving behavior. Based on historical examples and the experimental literature such nudge-based policy may be effective and cost-efficient if started now.

References

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed in events, policy briefs, working papers and other publications are those of the authors and/or speakers; they do not necessarily reflect those of SITE, the FREE Network and its research institutes.

Photo by Leonid Ikan, Shutterstock.com